This student study technique is perfect for any reader

The SQ3R method is a well-established reading strategy widely used in education to improve comprehension and memory retention (Sudarsono & Astutik, 2024).

Developed by Francis P. Robinson in his 1941 book Effective Study, the SQ3R method was designed as a self-directed learning aid to help students develop their study skills (Robinson, 1941).

The steps in SQ3R are Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review. Using these steps transforms reading from a passive activity into an active process of engagement, inquiry, and information-seeking (Walny et al., 2018).

But just how effective are these steps? This post explains each step, summarises supporting academic research, and explores modern adaptations of the technique. It is worth noting that the SQ3R method applies mostly to non-fiction books.

The following sections outline each stage of the SQ3R method:

Full Academic Paper (Open Access)

If you want the fully referenced academic version of this article, you can read it:

Survey

How to Apply:

Start by previewing the book to get a clear overview of its content and structure. Look at the title, blurb, contents page, and section headings, as well as the opening and closing paragraphs of each chapter.

How effective is Surveying?

Surveying a book before reading in full helps you build a mental outline of its structure, making it easier to organise and connect new information.

Skimming is considered one of the most valuable skills a reader can develop. It helps identify the purpose, topic, and key details of a text quickly (Brown, 2001).

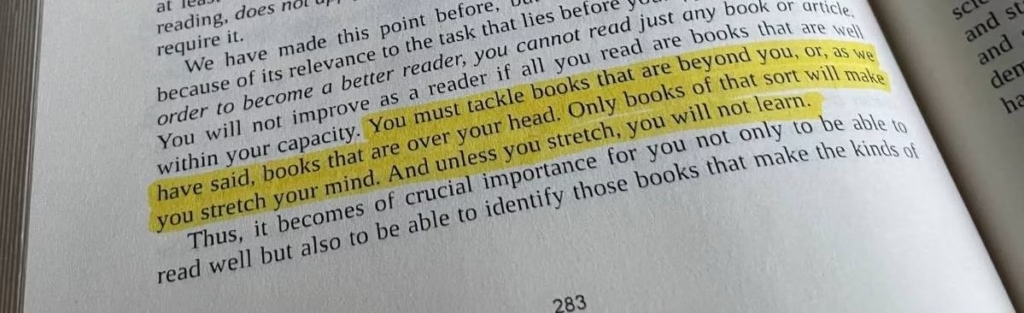

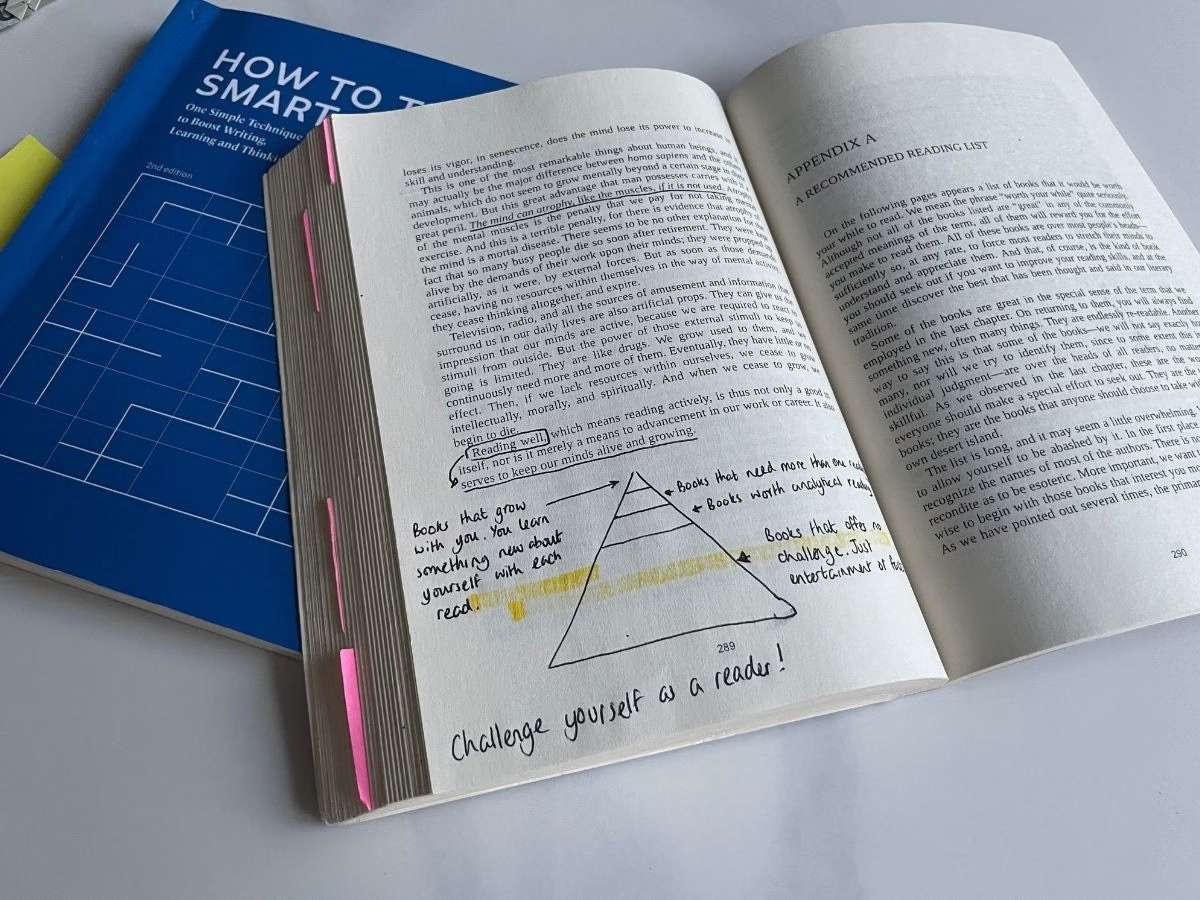

In How to Read a Book, Adler (1972) refers to this step as ‘Inspectional Reading’. It is an effective first step that builds a framework for the text’s arguments and helps readers decide whether the text merits deeper study.

Adler also recommends moving on to a different text if the book doesn’t align with your purpose after this initial survey. This early decision can prevent unnecessary time spent on the wrong books.

Question

How to Apply:

Before reading, identify what you want to learn. The SQ3R method suggests turning chapter headings and subheadings into questions, then reading each section to find the answers.

How Effective is Questioning?

Asking questions while reading encourages an active and creative approach. It supports deliberate thinking and improves clarity and comprehension (Suzanne, 2016).

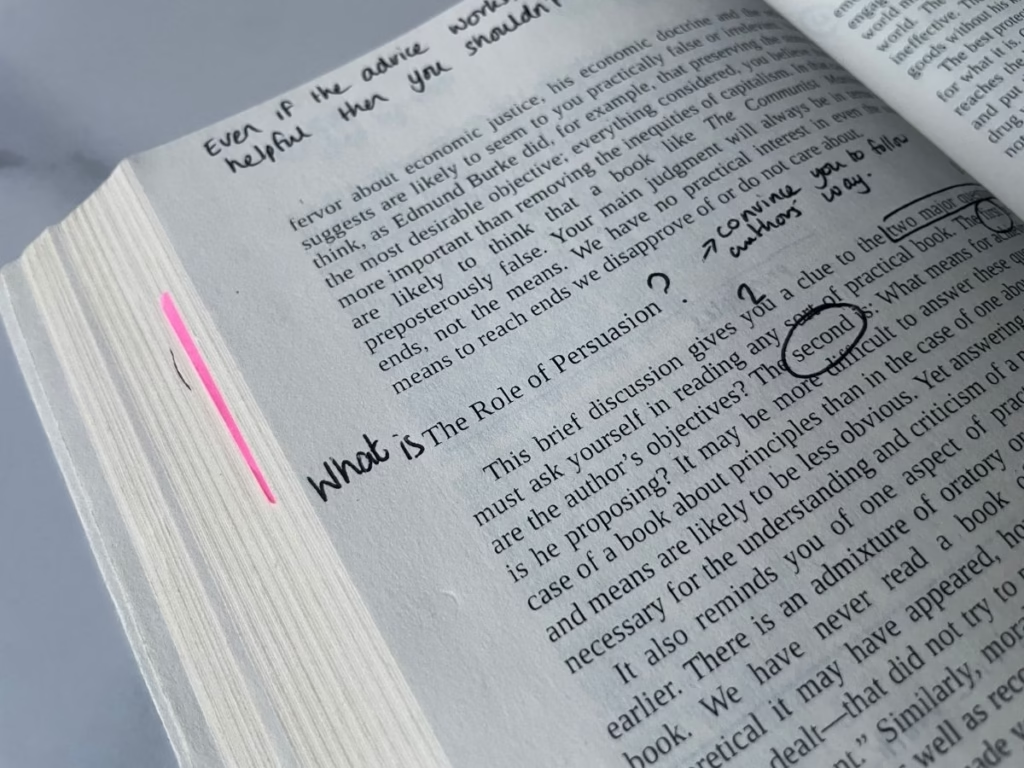

Adler (1972) outlines four key questions readers should ask. The final and most important question is ‘What of it?, which transforms knowledge into purposeful action by asking readers to apply what they’ve learned to their own lives.

In a classroom, the most engaged students are those who ask thoughtful questions. When reading, the author is absent, so it becomes the reader’s responsibility to ask questions and seek out the answers independently.

Read

How to Apply:

Now start reading, and read with a purpose. Use your questions to guide your attention and note any new questions that emerge.

How Effective is Reading?

To improve your active reading skills, take notes as you go. Note-taking, such as highlighting or underlining, helps readers stay focused and retain more information (Walny et al., 2018).

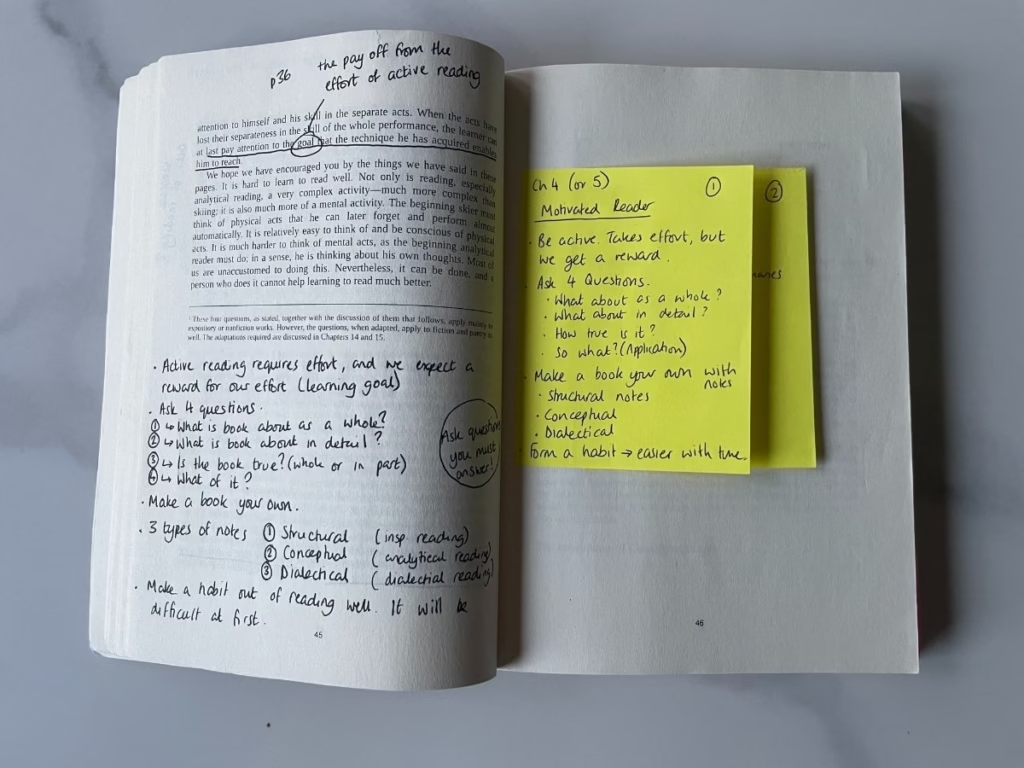

In How to Take Smart Notes, Ahrens (2017) argues that handwritten notes are more effective than typed notes. Writing by hand slows the process and allows the brain more time to consider the information. While typing is faster, it risks becoming a shallow, copy and paste transcription exercise.

Ahrens (2017) believed the SQ3R method to be overcomplicated at times, and promoted a simpler reading/note-taking system called Zettelkasten.

Recite

How to Apply:

After reading each section or chapter, summarise what you learned in your own words. Focus on the gist, and write it down to strengthen retention.

How Effective is Reciting?

Summarising helps readers process and organise information, build academic communication skills, and improve overall comprehension (Silveira, 2003).

Silveira (2003) outlines multiple summary techniques. Below is a condensed set of commonly used and effective practices:

Silveira’s Summary Tips

1. Identify the main idea and key points.

2. Use your own words and quote only when necessary.

3. Keep essential information and cut repetition or minor details.

4. Preview and plan by rereading, highlighting, and outlining before writing.

5. Be concise and clear, aiming for about 15–20% of the original length.

6. Stay objective by avoiding opinions or added examples.

7. Check understanding and ensure accuracy before finalising.

Review

How to Apply:

After reading, look over what you have learned. Read through your notes, test your memory, and identify any gaps in your understanding.

How Effective is Reviewing

In SQ3R, reviewing is not the same as rereading. Rereading alone can create a brief feeling of familiarity but does little for long-term memory. Ahrens (2017) links this to the Mere-Exposure Effect, where familiarity is mistaken for understanding.

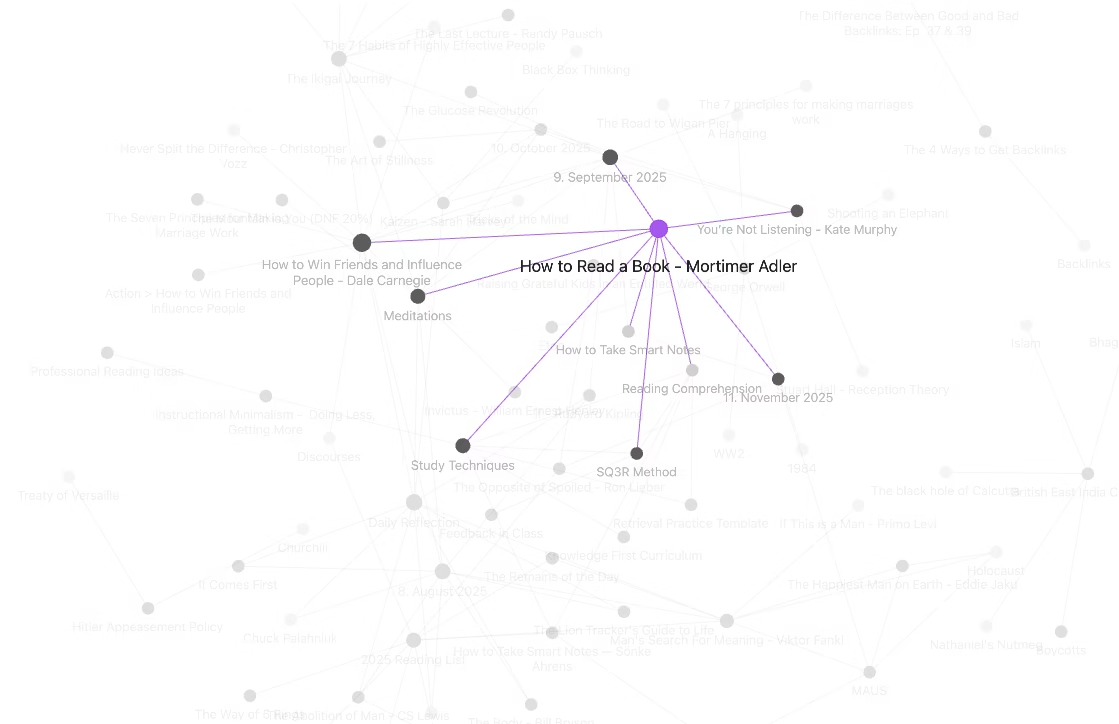

A more effective review approach is Elaboration, where you explain ideas in detail and connect new information to what you already know (Smith & Weinstein, 2016; Ahrens, 2017). This involves asking how and why questions and integrating the answers into your existing knowledge. Creating multiple connections forms a stronger foundation for recall (Weinstein, Madan, & Sumeracki, 2018).

Many active reading tips from the SQ3R method were included at the start of the famous How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936). See all the reading tips here.

Alternatives to SQ3R Method: SQ4R, SQ5R, SQ6R

Over time, educators and researchers have expanded the method to include additional steps. These variations aim to support deeper understanding and longer-term retention.

Different readers may benefit from adapting the method to their needs. Below is a summary of several additional steps that appear in common SQ3R variations.

Respond

This step encourages readers to evaluate the author’s explanations and evidence, forming a personal response to the material. It requires more specific and detailed answers to the claims made by the author.

Relate

This step involves linking new information to prior knowledge or personal experience to strengthen understanding. It is similar to the elaboration method mentioned in the review step. But if you feel a reminder is necessary, add this step.

Record

This step involves writing down answers to questions along with the summary (Al Halim, 2023). It closely overlaps with the recite and review stages of the original SQ3R method and adds little additional value.

Reflect

This step encourages readers to assess what they have learned and evaluate how well their approach supported their goals. Reflection can highlight areas for adjustment or improvement (Al Halim, 2023).

Revisit

This step extends the review process by increasing the time between returning to the material. This form of Spaced Practice is strongly associated with long-term retention and is regarded as one of the most effective study techniques (Dunlosky & Rawson, 2015; Weinstein, Madan, & Sumeracki, 2018).

The Best Fit for You

The individual steps in the SQ3R method are widely recognised as effective reading strategies, and each one can help shift reading from a passive to an active pursuit.

You can apply these steps in any order or adapt them to your needs. Not every book requires the full method, so choose the steps that match your purpose. The research cited in this post shows that even using one or two of them can strengthen both comprehension and long-term recall.

If you found the SQ3R method helpful, there are plenty of other study techniques that are perfect for busy readers:

Further Reading

Traynor, N. (2025). The SQ3R Method: An Evaluation of Its Effectiveness and Applications. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17728256

References

Al Halim, M. L. (2023) ‘Improving students’ reading comprehension through SQ5R methods: A distance learning during the pandemic COVID-19’, Lingua Scientia Jurnal Bahasa, 15(1), pp. 141-162. doi: 10.21274/ls.2023.15.1.141-162. (Link)

Adler, M.J. & Van Doren, C. (1972) How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading. New York: Simon & Schuster

Ahrens, S. (2017) How to Take Smart Notes. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Brown H.D. (2001). Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy: Second Edition. New York: Longman (Link)

Dunlosky, J. & Rawson, K.A. (2015) ‘Practice tests, spaced practice, and successive relearning: Tips for classroom use and for guiding students’ learning’, Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1(1), pp. 72–78. (Link)

Palmer Silveira, J.C. (2003) ‘Summarising techniques in the English language classroom: An international perspective’, PASAA, 34 (December), pp. 54-63 (Link)

Pilat, D. & Krastev, S. (2021) ‘Mere Exposure Effect’, The Decision Lab. Available at: https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/mere-exposure-effect (Accessed: 8 November 2025).

Robinson, F. P. (1941) Effective Study. New York & London: Harper & Brothers. (Link)

Smith, M. & Weinstein, Y. (2016) Learn how to study using… elaboration. The Learning Scientists. Available at: https://www.learningscientists.org/blog/2016/7/7-1 (Accessed: 5 November 2025).

Sudarsono, F.W. & Astutik, Y. (2024) ‘Evaluating the effectiveness of the SQ3R method in enhancing students’ reading proficiency.’ Script Journal: Journal of Linguistics and English Teaching, 9(1), pp.24-41. doi:10.24903/sj.v9i1.1598. (Link)

Suzanne, N. (2016) ‘Being active readers by applying critical reading technique’. Ta’dib, 14(1). DOI: 10.31958/jt.v14i1.197. (Link)

Walny, J., Huron, S., Perin, C., Wun, T., Pusch, R. & Carpendale, S. (2018) ‘Active Reading of Visualizations’, IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 24(1), pp. 770-780. doi: 10.1109/TVCG.2017.2745958. (Link)

Weinstein, Y., Madan, C.R. & Sumeracki, M.A. (2018) ‘Teaching the science of learning’. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-017-0087-y

Leave a Reply